Work History: Rec Room - Principal Software Architect

What I did as a Principal Software Architect at Rec Room from 2021-11 to 2024-11.I excelled as a Senior Software Engineer at Rec Room. Although we never used formal titles, I was promoted to the highest level of the engineering ladder and referred to as "architect". As the Logic Team grew, we brought on a principal designer, Audrey Cox, and an engineering manager, Jason Young, allowing leadership responsibilities to be distributed across a broader team. Our scope expanded beyond Circuits to include all creation primitives. Over the next three years, we continued to evolve the technology and scale the organization so that millions of creators and hundreds of engineers could contribute to Circuits.

Table of Contents:

The Logic Team grew rapidly during this period. The team expanded to a peak of 18 FTEs, and employees across the 300-person company built features that integrated with our technology. At its height, I was responsible for roughly 15% of all company code reviews. This was a signal that the model didn't scale.

To resolve our scale problems I worked with Rec Room CEO Nick Fajt and VP of Engineering David Haley to develop a framework where our team never had to say "no." When we disagreed with an approach, the goal was to point it in the right direction rather than block it indefinitely. We might prevent code from merging, but we always provided clear line-of-sight to the next milestone. Most of my time over this period was focused on processes and technology that made the "never-be-a-blocker" approach possible.

As a result, I made fewer direct contributions to individual projects, but provided technical guidance across many of them. Highlights include:

| Animation Gizmo V2 |

| Audio Player Custom Falloff |

| Cloud Lists |

| Color Type |

| Combat HUD UI |

| Comment Chip |

| Data Table |

| Debug Execution Tool |

| Dev-Only Chip Containment |

| Doors V2 |

| Environments |

| Equip Chips |

| Explosion Emitter |

| Get Room Is Private Instance Chip |

| Grabber |

| Handles |

| Home Values |

| Interaction Roles |

| Interim Multiplayer Integration Tests |

| Invisible Collision V2 |

| Laser Pointer |

| Logging Improvements |

| Moods V2 |

| Non-Compiled Functions |

| Object Model Circuits Integration |

| Object Properties |

| Player Get Time Zone |

| Player Prompt Multiple Choice |

| Player Properties |

| Player Tags |

| Player World UI |

| Port Hover Type Display |

| Progression System |

| Projectile Launcher |

| Respawn Support |

| Room Leveling System |

| Room Reset |

| Room Set Matchmaking State |

| Sampler V2 |

| Set Position Chip |

| Share Cam Used Event |

| Spawn Point V2 |

| State Machine V2 |

| Switch Chips |

| Synced Immutable Lists |

| Tags |

| Text Get Color |

| Text Screen |

| Tool Respawn |

| Welcome Mat V2 |

| Wire Flash Debugging |

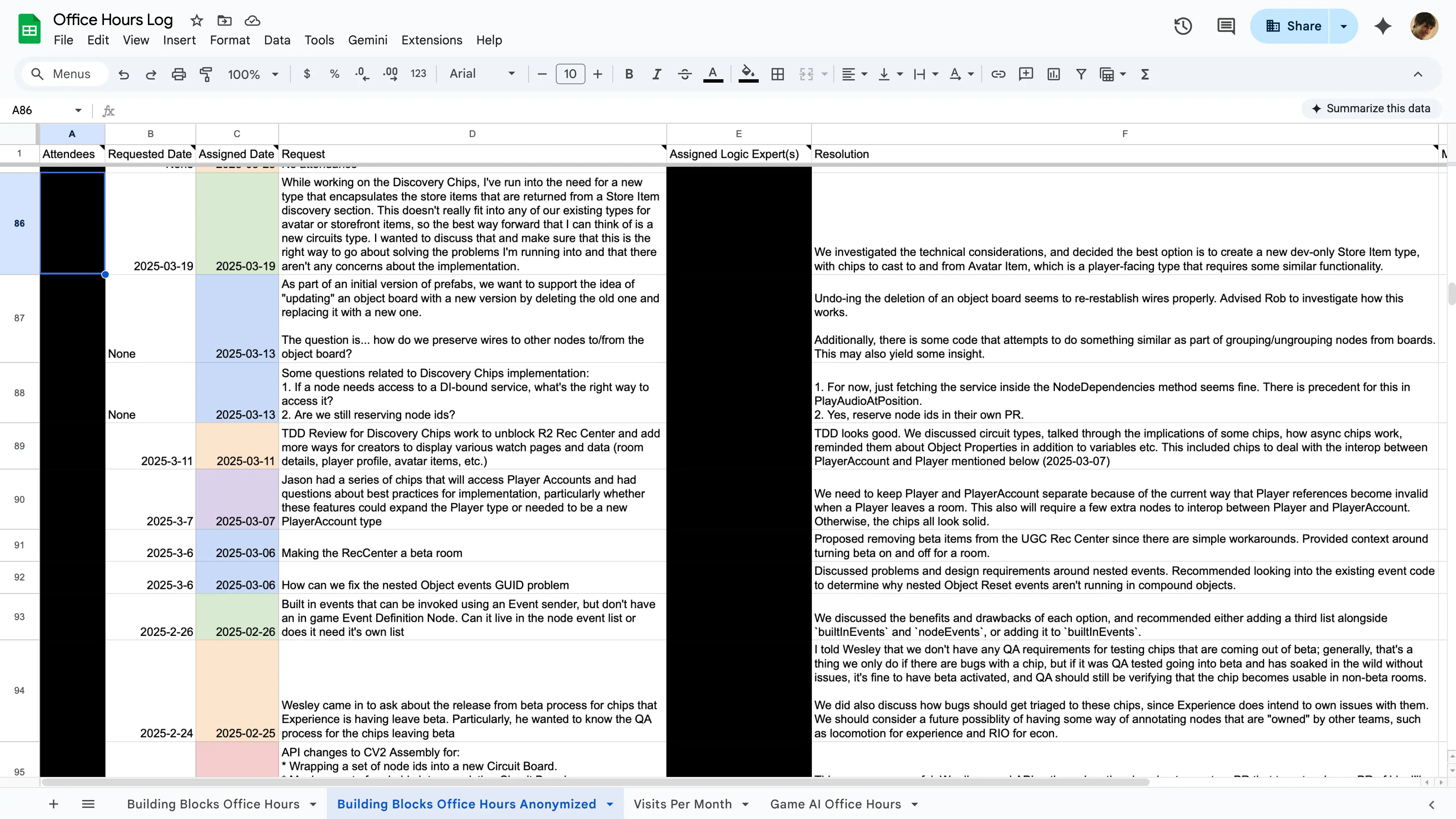

The most impactful change we made to scale the team was evolving my personal office hours into Logic Team office hours. I worked with other teams to produce a memo outlining how we would scale the program. Initially, I kept a daily 11:00-12:00 slot open on my calendar for anyone with urgent requests. Over time, we began having senior engineers shadow me during office hours and gradually take on providing feedback themselves. Eventually, I was able to step back to a single weekly slot instead of hosting office hours every day.

It may sound small, but office hours was beloved across the company. The Logic Team valued the opportunity to help and to get exposure to a wide range of projects, while other teams appreciated having a reliable way to get unblocked. We maintained a shared log of requests, which allowed hosts to quickly see where the previous session left off and identify common themes across issues. Looking back through that log now, I'm thrilled to see that we helped hundreds of people over the years.

Adam Dormier, one of our top engineers, also developed a new employee orientation program in which every new hire, across engineering, design, HR, finance, and other roles, learned about Circuits. This ensured that everyone joining the company understood how Creators operated within our ecosystem, helping ground their decision-making from day one. While I wasn't directly involved in creating the orientation, it's worth highlighting as part of the broader culture of learning I worked to establish. I was especially proud to see an engineer independently identify this need, pursue it in his own time, and deliver a program with lasting impact.

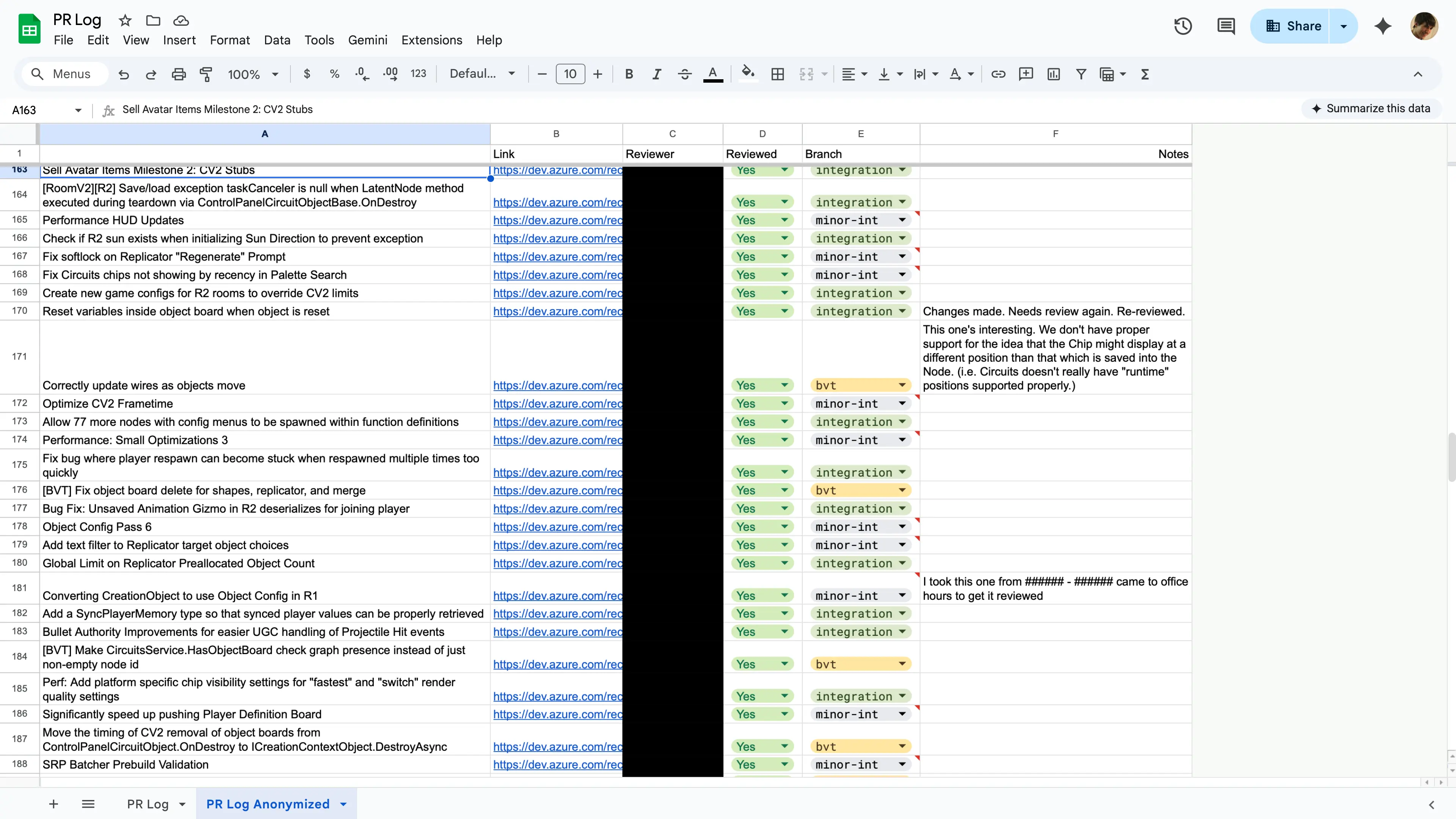

To help distribute code reviews I established clear code quality guidance in four ways:

- I formalized our code review standards in a written memo so teams knew what to expect.

- I formalized a TDD process with documentation, a template, and examples.

- I created a consistent checklist outlining what we evaluated in every code review.

- I maintained a code review log to assign code reviews to developers, track decisions, and surface recurring issues.

The log was the most impactful part of this change. Previously, responsibility was diffuse because any engineer could assume that someone else would handle it. Introducing the log made ownership explicit, which turned out to be a relief. Engineers were happy to take responsibility when expectations were clear, rather than being asked to pick up code reviews at random on top of their existing work.

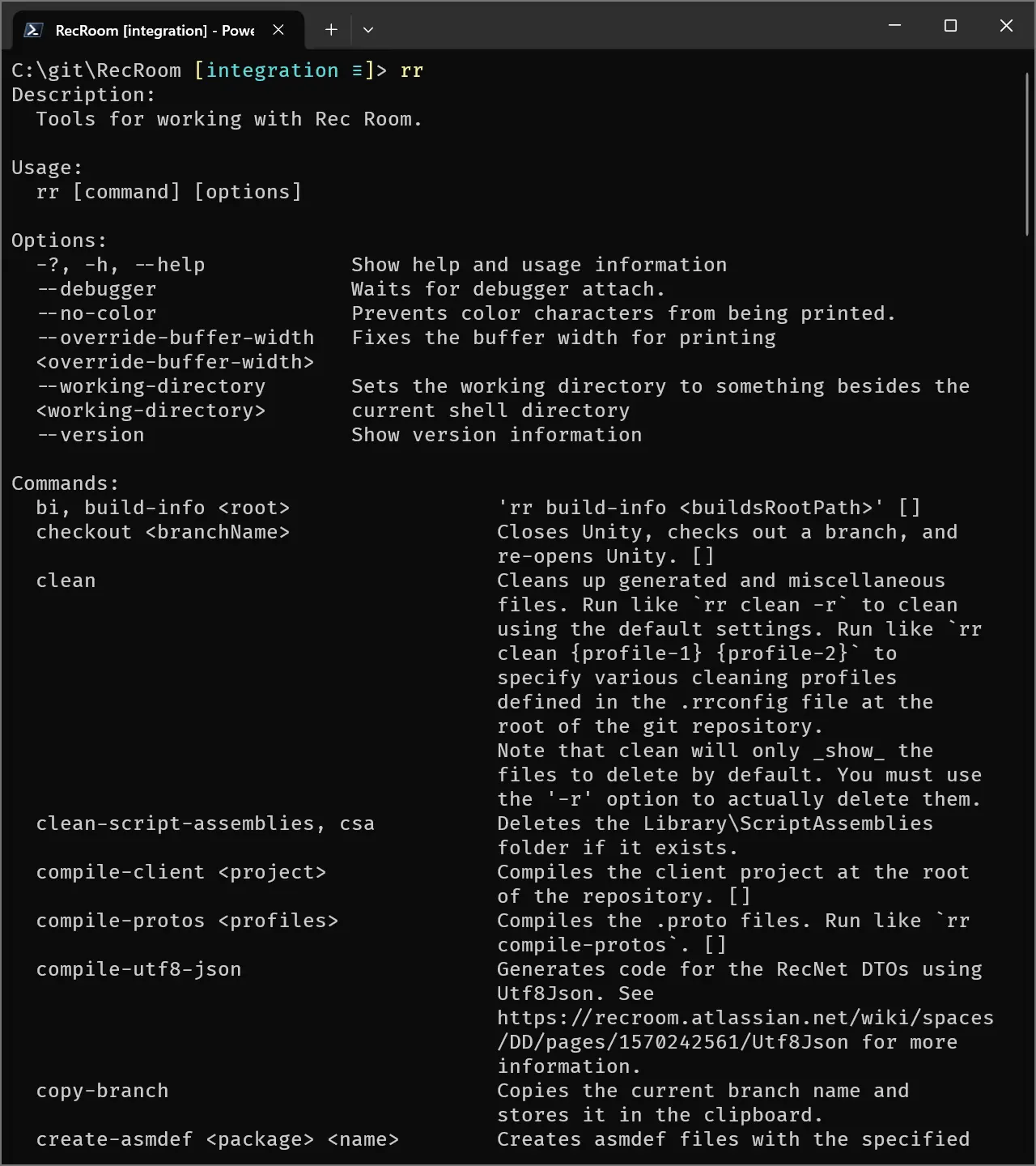

rr was a command-line tool I built to unify a growing set of internal utilities into a single, shared platform. It replaced a fragmented ecosystem of scripts and one-off tools with an extensible system that any team could adopt and contribute to. Previously, tools were passed around via Slack messages or buried in Confluence pages, making discovery dependent on knowing the right person. While the immediate goal was to streamline our own Circuits workflows, the broader impact was improved tooling adoption and collaboration across the company.

I built rr on top of Microsoft's System.CommandLine library and structured it as a host for shared utilities exposed as subcommands. For example, rr analyze-assemblies analyzed our assemblies, while rr compile-protos handled protobuf compilation. I also added rr create-cmd, which scaffolded a new rr subcommand by generating a new assembly with all required prerequisites in place.

To remove friction, I shipped a double-click installer and migrated as many Logic Team and company tools as possible into rr. I also presented a short how-to during our Dev Talk lunch series. Adoption was immediate since the tool made discovery trivial and getting started was effortless.

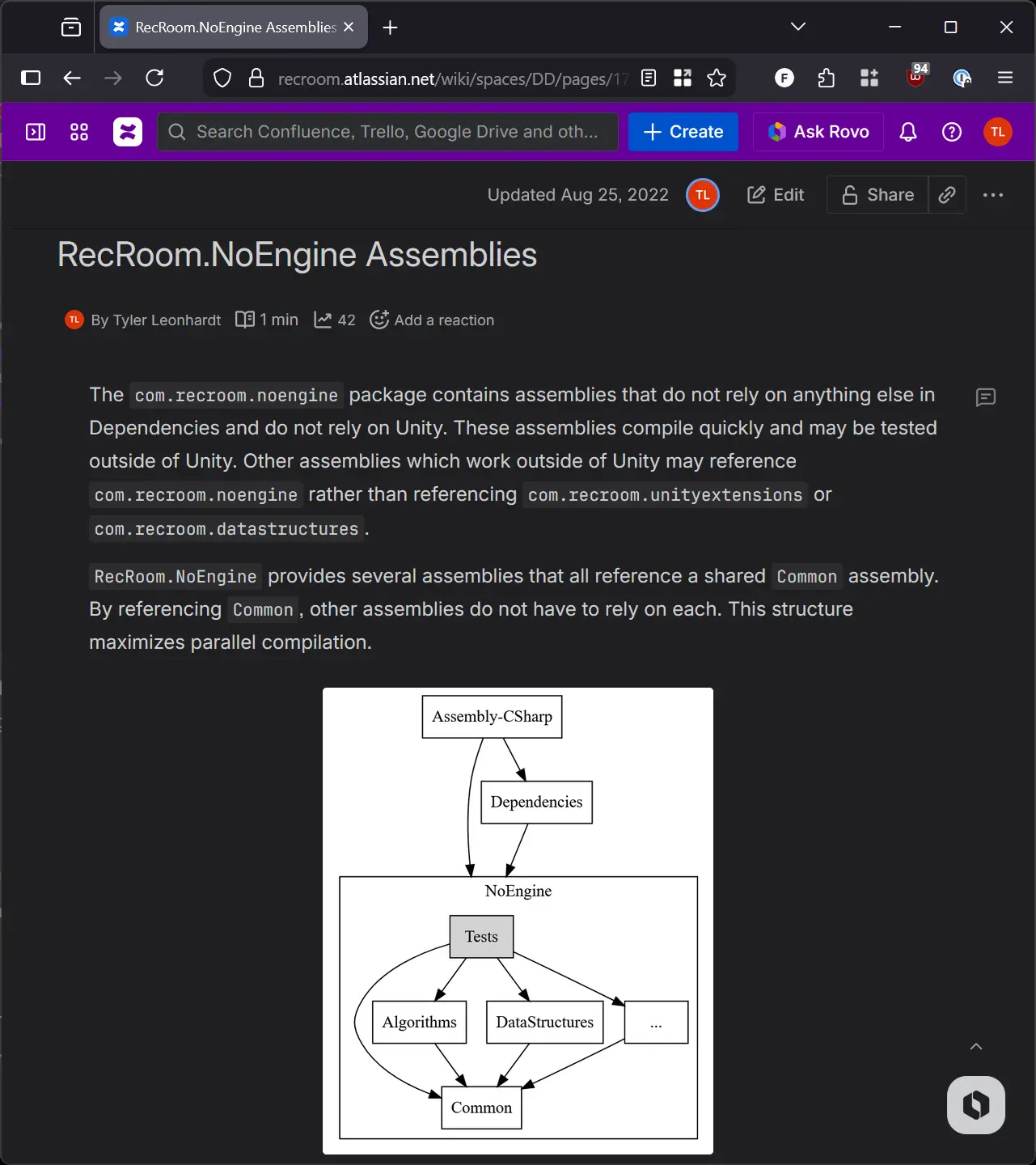

No Engine was a rewrite of critical company code that established the foundational layer of our codebase. The goal was to remove dependencies on Unity from our most fundamental systems, particularly Circuits, so that they could be more easily adopted across other projects at the company. We found that this approach had unexpected workflow and stability benefits too.

No Engine was a large undertaking, completed primarily by myself and Kartik Agaram. I began the project before Kartik joined by building an internal rr tool, rr hydrate-noengine, which analyzed a Unity project's structure (package-lock.json, manifest.json, package.json, and .asmdef files) and emitted .sln and .csproj files free of Unity dependencies. This required .asmdef files to opt in via "noEngineReferences": true.

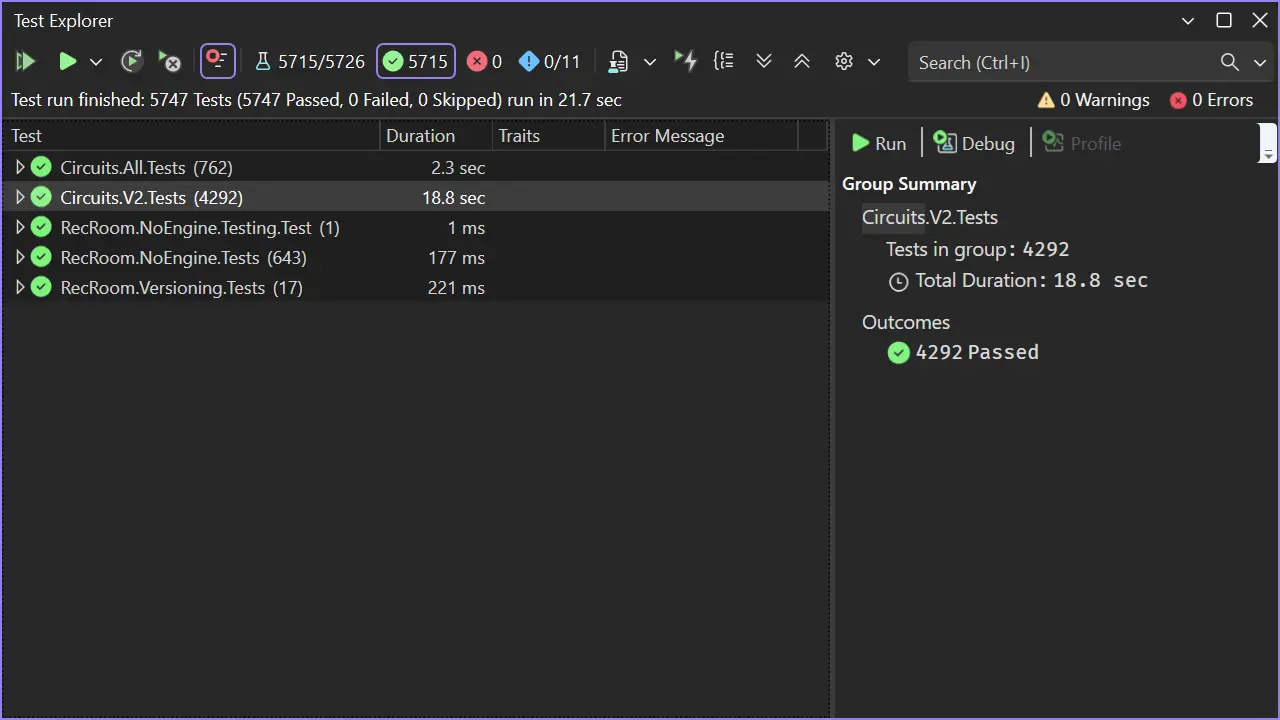

With the tooling in place, Kartik and I started migrating code into the No Engine layer of the Rec Room codebase, and the benefits were immediate. Unit tests ran hundreds of times faster than they did inside the Unity editor, making tests the path of least resistance for development. As a result, engineers naturally wrote more tests, dramatically improving the stability of our most critical code. Circuits alone grew by thousands of tests. IDE tooling and static analysis also worked far better outside of Unity. This transformation made the codebase significantly more pleasant to work in, further accelerating development and raising the overall quality bar.

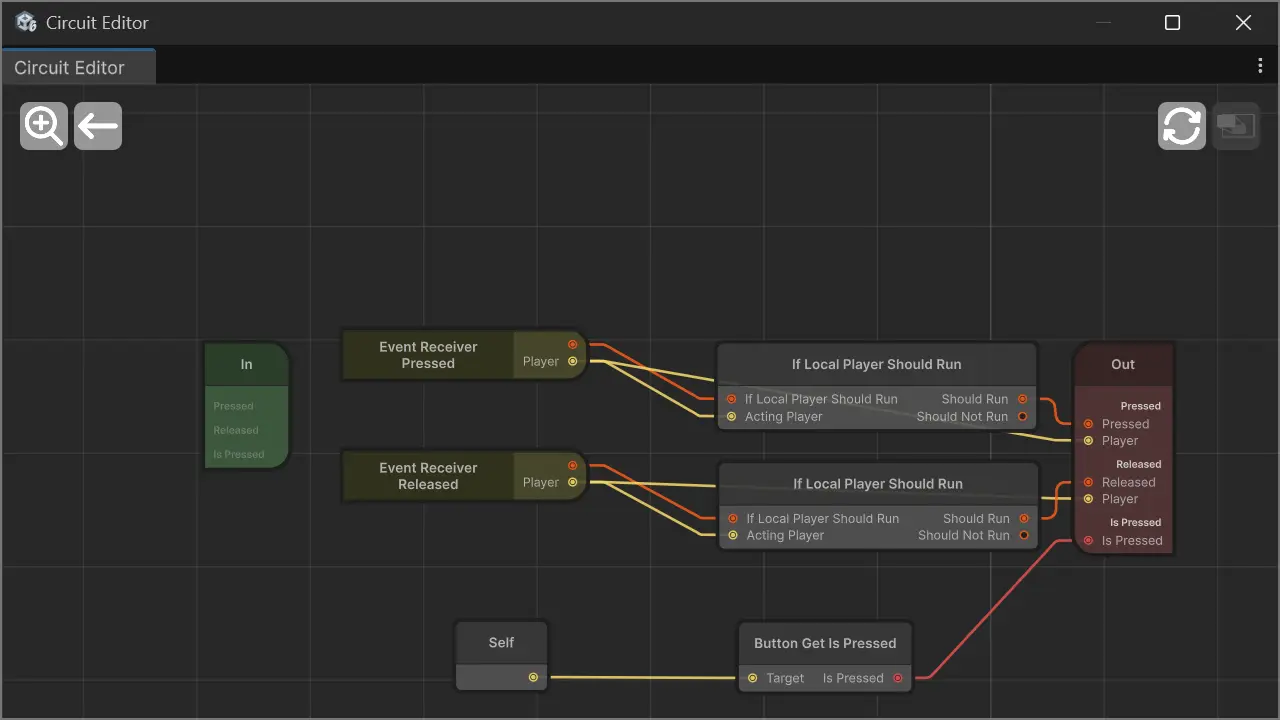

As the company scaled, we looked for a step-change in what creators could build. Even with a strong team, there was a ceiling to what we could achieve by building tools from scratch, and we knew there had to be a better way. To address this, we launched Rec Room Studio, which allowed creators to build Rec Room content directly in Unity using its world-class toolset. As the project matured, we made a decision to bring Circuits into Rec Room Studio as well, ensuring creators could retain the tools and workflows they already loved.

This integration was made significantly easier by earlier work to move Circuits onto the No Engine framework. As a result, bringing Circuits into Rec Room Studio introduced no unexpected dependencies. The same dependency-injection system that allowed Circuits to run both in-game and standalone seamlessly accepted dependencies from Rec Room Studio. In practice, we were able to drop Circuits into the Rec Room Studio .asmdef files and treat the dependency graph as a specification for what still needed to be built.

This project was another huge success for Circuits and continued to expand the surface area to a new platform and more people--professionals, who could really push the tools to their limit.

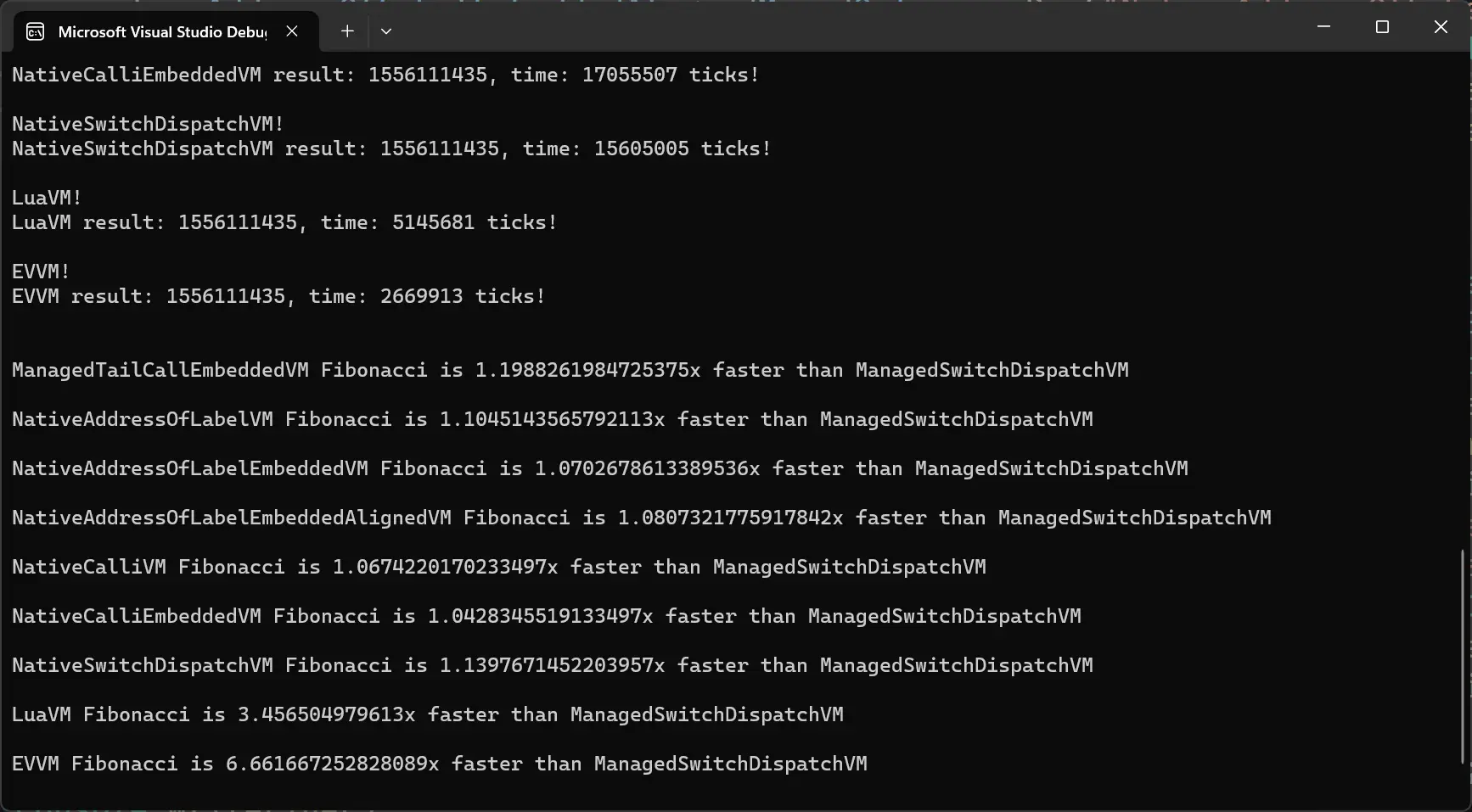

The final project I worked on as Circuits Architect was a compiler for Circuits. The system was originally built on an interpreter, which imposed hard limits on runtime performance. Kartik Agaram and I spent roughly a year building a framework to port nodes to what we called Compiled Circuits. The result delivered 7x performance improvements, introduced new creation primitives, and resolved several long-standing memory issues.

Despite the investment, we ultimately chose not to ship Compiled Circuits. Sometimes the superior technology isn't the right decision in the moment, regardless of how much work has gone into it. About three-quarters of the way through the project, we hired Mark Domowiczonto the Logic leadership team as Product Lead. Mark brought deep experience from his time on a management team at Skydance.

Mark challenged the assumption that we needed a full compiler to achieve our most important goals. Under his guidance, we spun up two simpler, incremental efforts alongside Compiled Circuits: Cheap Replicas and Non-Compiled Functions. I helped with the initial planning to get a small team moving in this direction.

We found that these two projects delivered most of the benefits with far less complexity. Compilers are inherently difficult, and we didn't have the bandwidth to bring the broader team up to speed on that stack. Additionally, porting thousands of chips one by one extended the timeline by months, while the non-compiled solutions were ready as soon as the core technology landed.

With Mark's help, we concluded it was better to take the well-worn path rather than distract ourselves with shiny technology. It was a critical call and I learned a great deal from Mark through that decision-making process.

As with my time as a senior engineer, I took on several responsibilities outside the Logic team during this period. While leading the team reduced the time I could spend in this area, I still contributed meaningfully to a few major efforts:

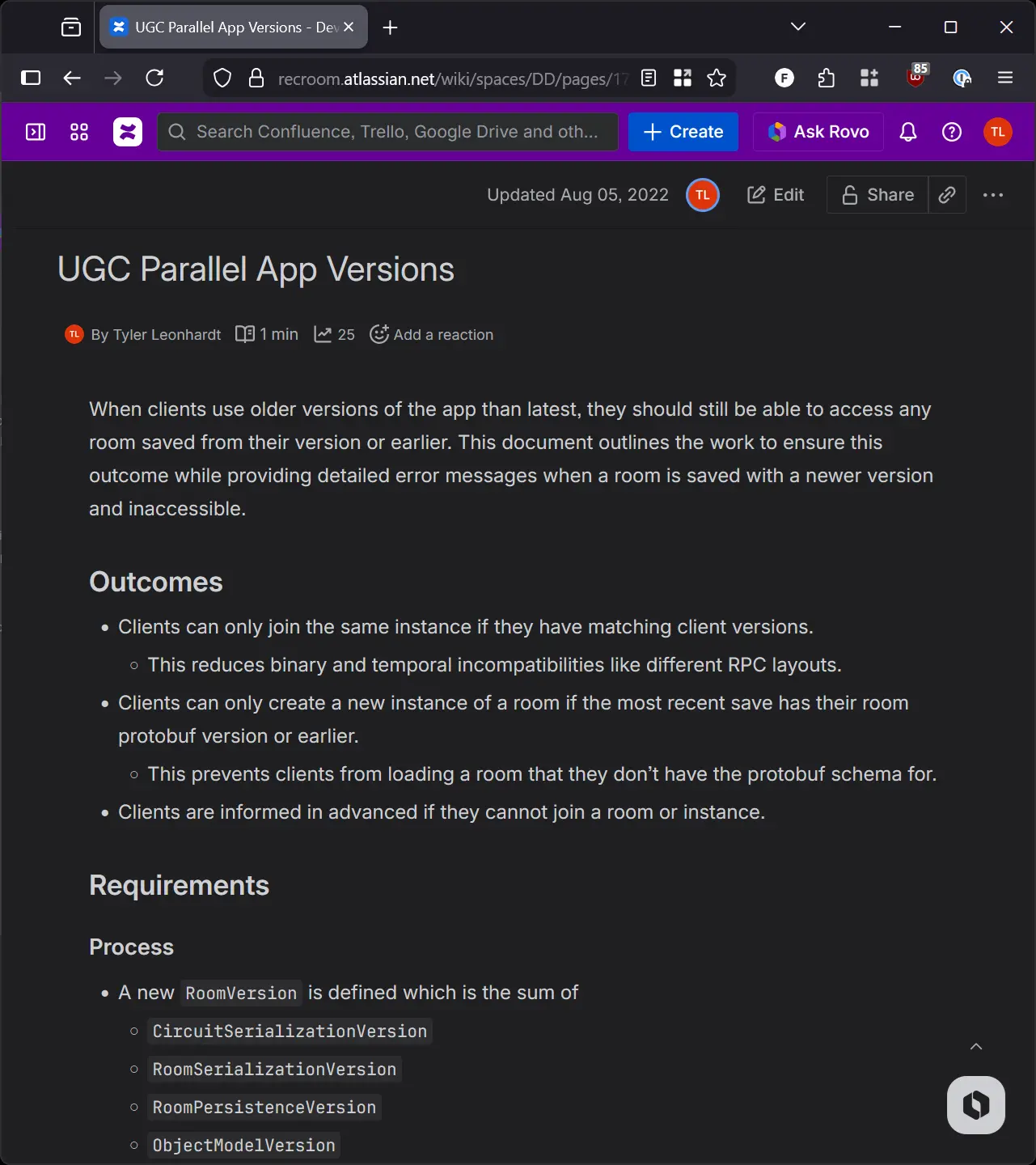

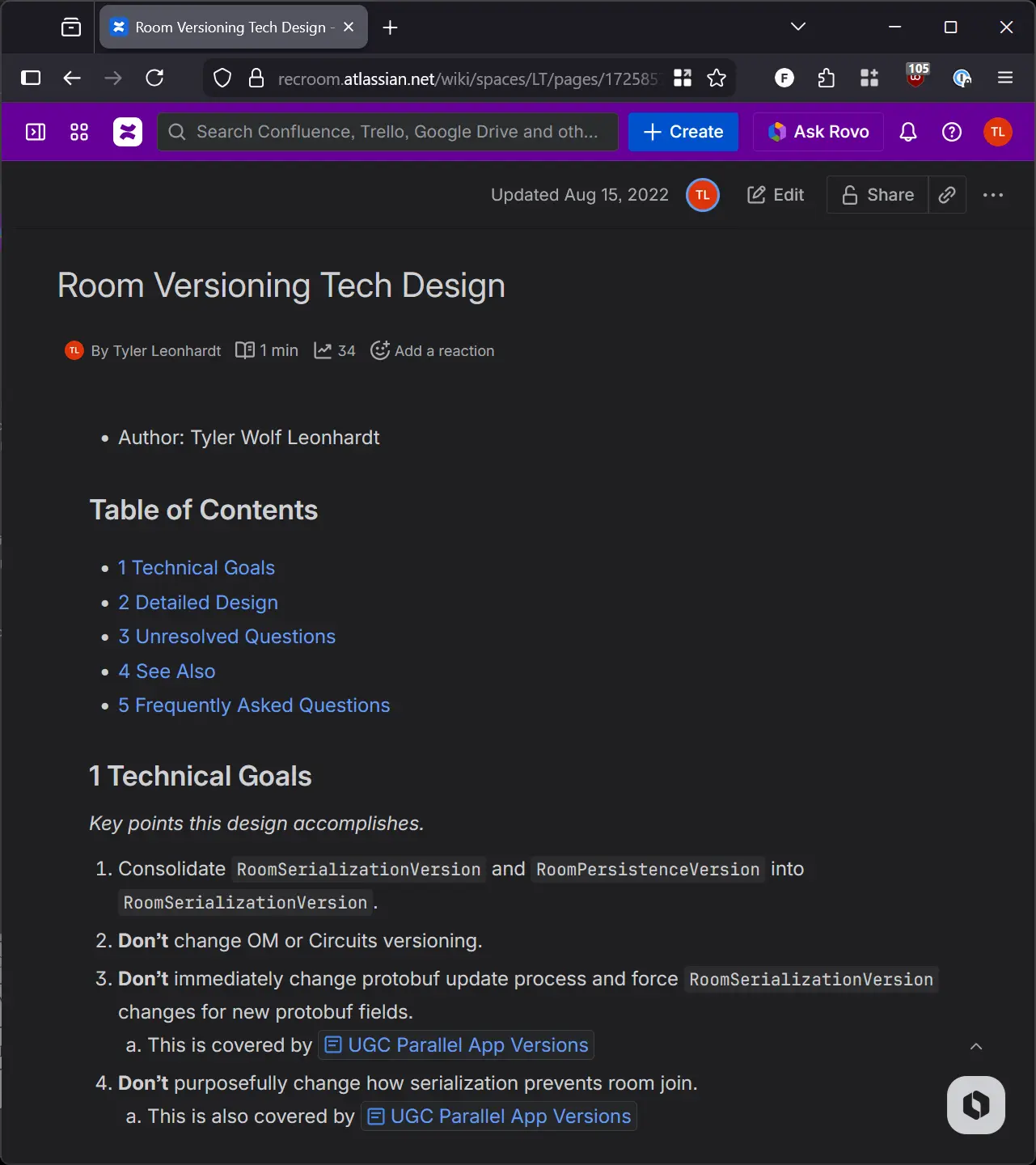

Our VP of Engineering, David Haley, asked me to help address a player engagement issue tied to our release cadence. Rec Room shipped weekly, and each release required players to download a new build. While this ensured a steady stream of fresh content, the friction of frequent reinstalls led to measurable player drop-off. The goal was to allow older builds to remain live for longer.

The core challenge was that our versioning model assumed a single, always-up-to-date client. Because every player was expected to be on the latest version, the system wasn't designed for old and new clients to coexist. Circuits, however, already had a robust solution: a monotonically increasing version number that developers incremented on breaking changes, paired with optional data converters to upgrade older data into newer formats.

In Circuits, we could simply prevent players from loading into newer rooms if their client's monotonically version was older than the room's data. We needed that same capability across the rest of the game.

I wrote a TDD outlining an approach to consolidate our disparate versioning systems and worked closely with Will Chilcote to implement it. In just a few weeks, we migrated all UGC to the new versioning model, allowing older builds to coexist safely with newer ones.

As part of a broader code-quality initiative, we set out to clean up our built-in logging utilities and migrate the organization to the debugging tools I developed. Our initial plan was to scan the codebase with a custom script and surface errors during continuous integration, but I pushed back on this approach because it didn't scale well to other classes of problems.

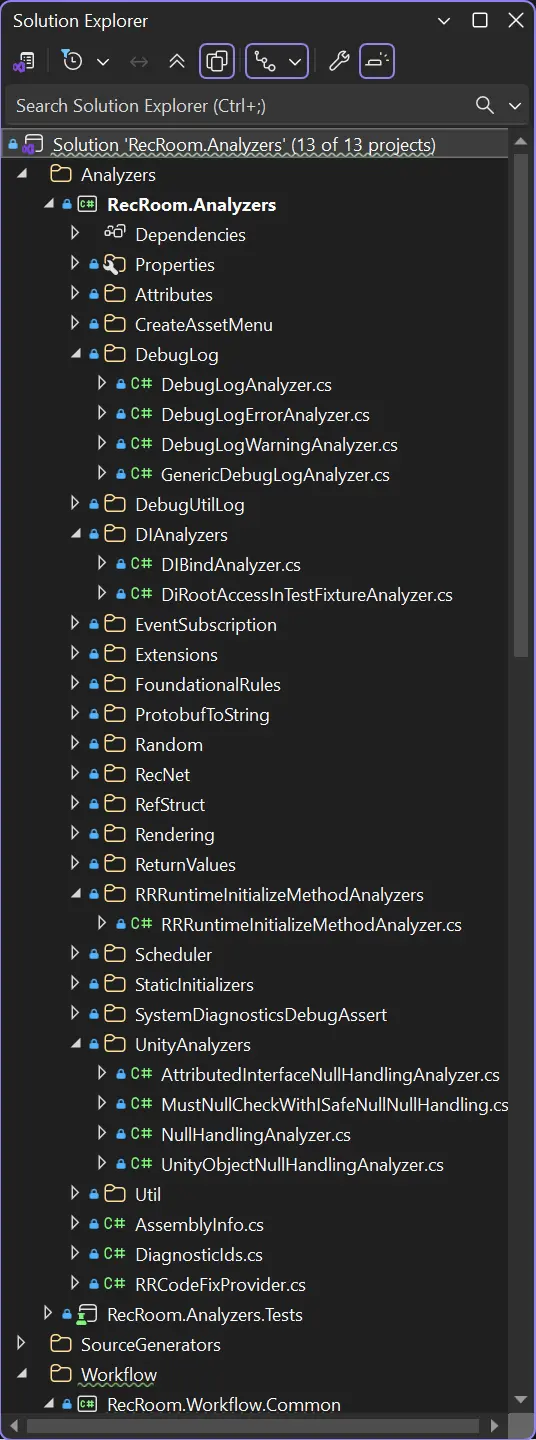

While researching alternatives, I discovered that our version of Unity supported Roslyn analyzers. I partnered with the team building the code-scanning tool to guide their solution toward a Roslyn-based approach. Using our existing rr toolset and lessons learned from No Engine, we stood up a dedicated analyzer project tailored to our needs.

This not only solved the immediate logging issue, but established a foundation for a wide range of future code-quality tools. Because the analyzers followed standard Roslyn patterns, they were easy to adopt and extend, and developers could rely on existing documentation to build new capabilities without bespoke tooling.