Work History: The Ohio State University - Software Engineer Lead

What I did as a Software Engineer Lead at The Ohio State University's Fundamentals of Engineering Honors program from 2012-08 to 2015-05.Table of Contents:

Skills: C, C++, C#, Leadership, and XAML

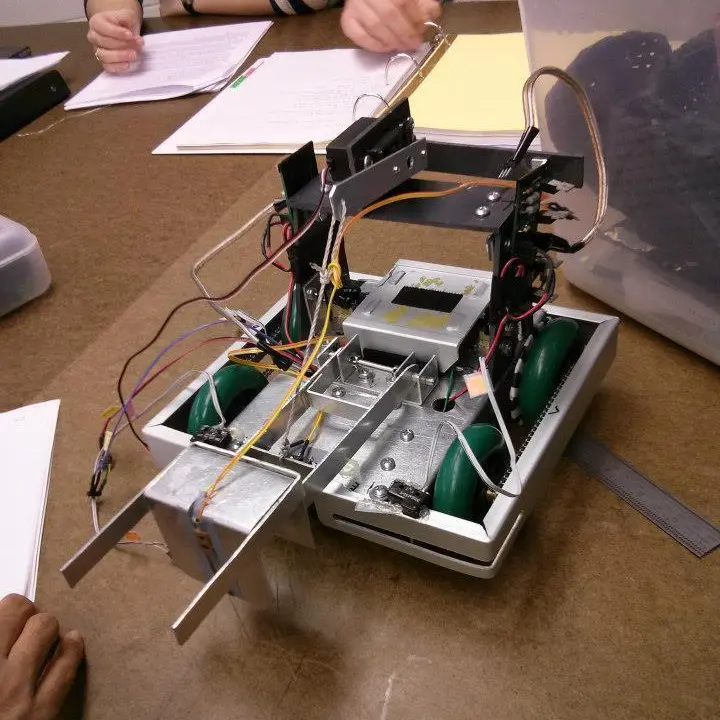

I served as the software lead for our autonomous robot competition teaching team. The robot competition was the capstone of our Fundamentals of Engineering Honors curriculum. Students competed in teams of four to design, build, and program autonomous robots which navigated a physical course and accomplished various tasks. The competition was held once a year with ~70 student teams.

This was a special moment because it was my first leadership position. I was already a strong software engineer but I had a lot to learn about leadership. I suddenly found myself working with a handful of exceptional teammates. It was exciting, but I struggled to support less experienced contributors. My guidance to novices often boiled down to vague direction like, "add to the software," which is embarrassing to admit now. I excelled at integrating systems from our top performers, but I often worked extra hours to make up for gaps in the work of junior staff.

Despite my struggles, we built a ton of quality software:

- An online store where students bought robot parts using Ruby on Rails

- Low-level software including an operating system running on custom circuitboards and microcontrollers

- A computer vision system to detect the robot position and orientation with QR codes using OpenCV

- Wireless communication software for XBees

- An SDK used by students to develop robot logic

- A framework for operating the robotics courses which provided a high-level UX integrated with the other low-level components

- Scoreboard software to display results in an arena

Each of these projects had a rockstar engineer behind it, so my job was mostly system integration. I attribute my success in large part to my team's skills since they could operate effectively without mentorship--they just knew what to do. I held the lead role for three years, and during that time my "add to the software" coaching grew into more actionable feedback. By the end, I trained the next generation of TAs and cleanly handed off the codebase.

Here is an overview of the competition from my former student, Carter Hurd:

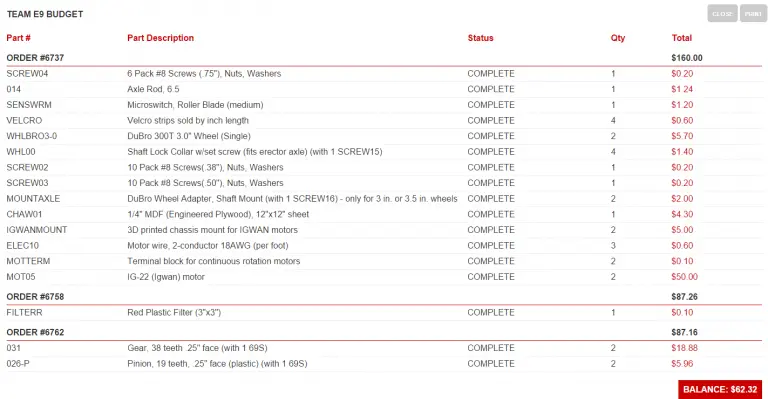

The online store was built using Ruby on Rails by Calvin Goodman. It allowed students to spend their pre-allocated budget on robot parts like sensors, motors, and other components.

Since the store didn't interface directly with the robot hardware, Calvin was able to develop it independently. We gave him space and stay out of his way. He was a reliable and gifted engineer.

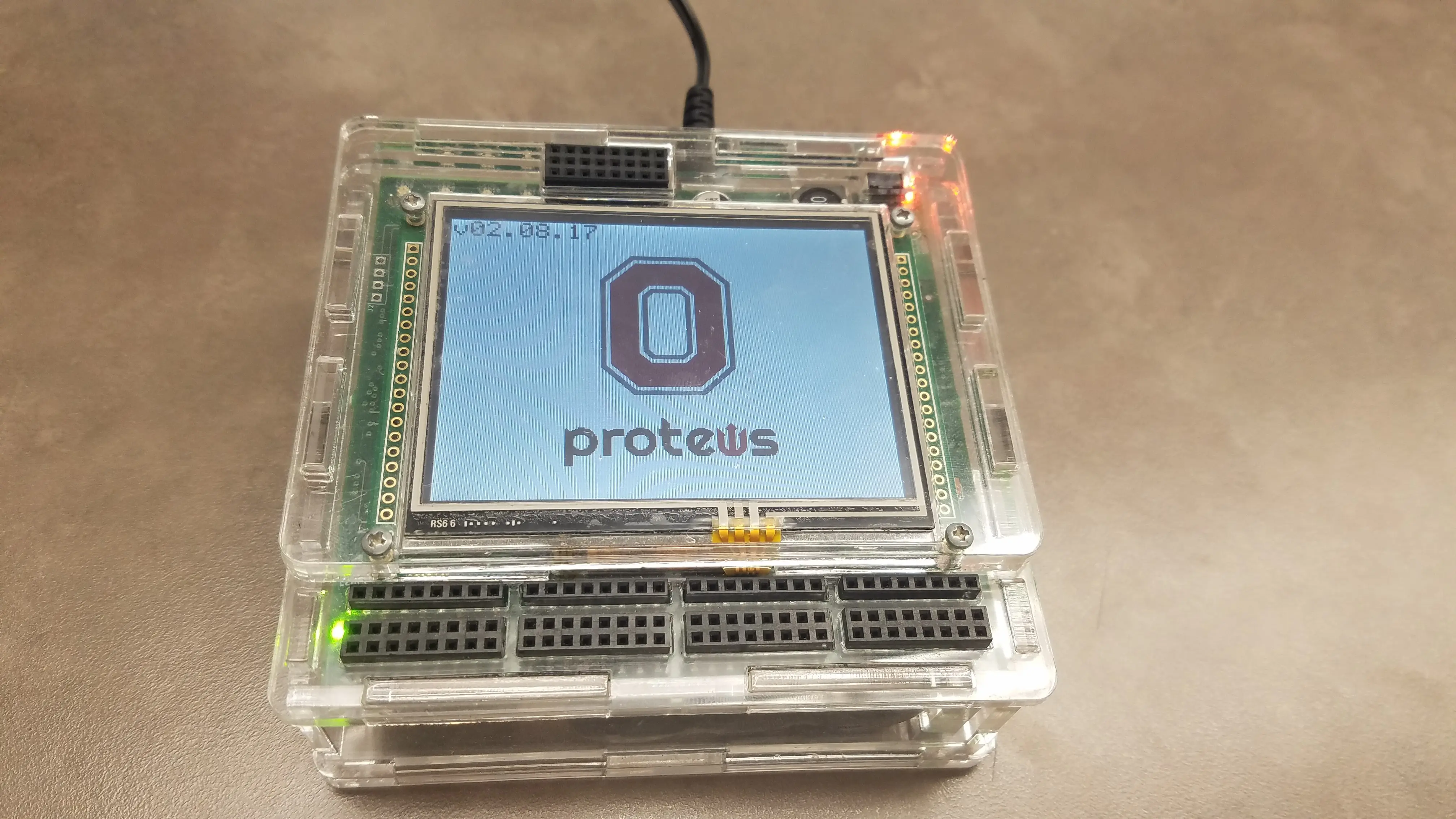

The Proteus was a custom microcontroller we developed as the brain of the robots. My boss, Michael Vernier, led its design and implementation. It featured a touch screen, a rechargeable battery, and a wide range of sensors and communication interfaces for components like CDS cells, servos, and motors. Michael built the Proteus end-to-end--from the circuitboards we printed and soldered to operating system we wrote byte-by-byte--this left the rest of the software team with an excellent foundation on which to build the SDK.

The Robot Positioning System (RPS) was a computer vision pipeline that provided real-time position and orientation data for every robot on the course. Students used this live tracking feed to build autonomous navigation software.

In my first year leading the program, we reused a simple infrared-based approach from prior years: each robot carried two IR LEDs on its chassis, and a sensor mounted above the course triangulated the position and heading. This was the same technique used by Wii controllers.

In my second year, we hired the excellent Ryan Niemocientski who built a more robust camera-based system using QR codes. We mounted overhead cameras to capture continuous video of the course, attached an upwards-facing QR code to each robot chassis, and used OpenCL to position the codes in realtime.

The RPS communicated with the robots through the course software. Ethernet was fed from the positioning system above the course, down one of the supports, and into a network switch below. Some custom circuit boards connected to the switch provided XBee wireless communication to the robots.

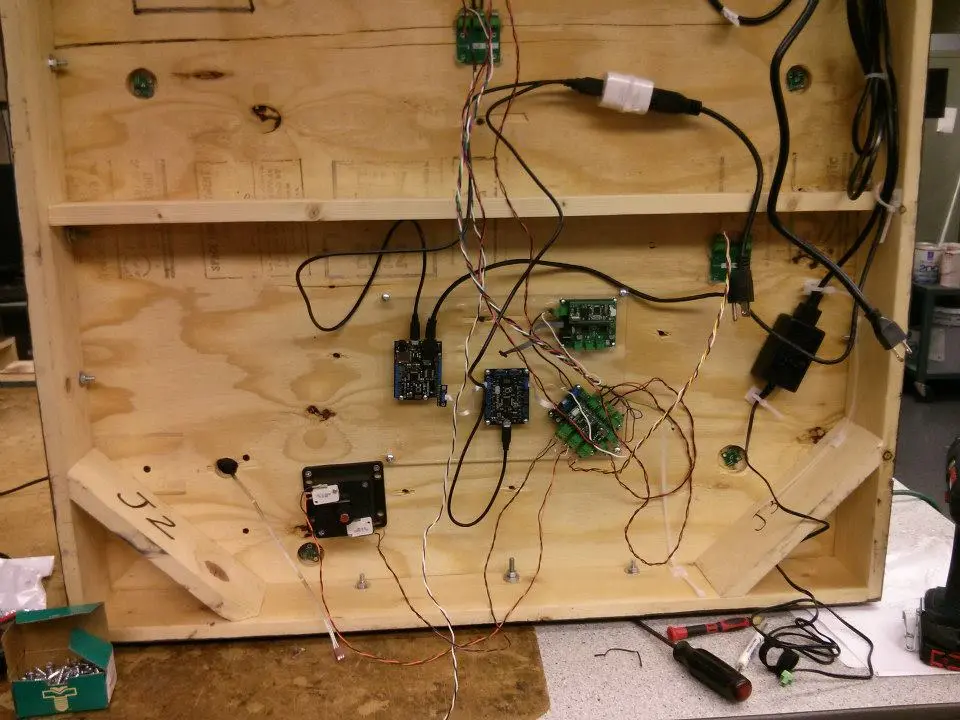

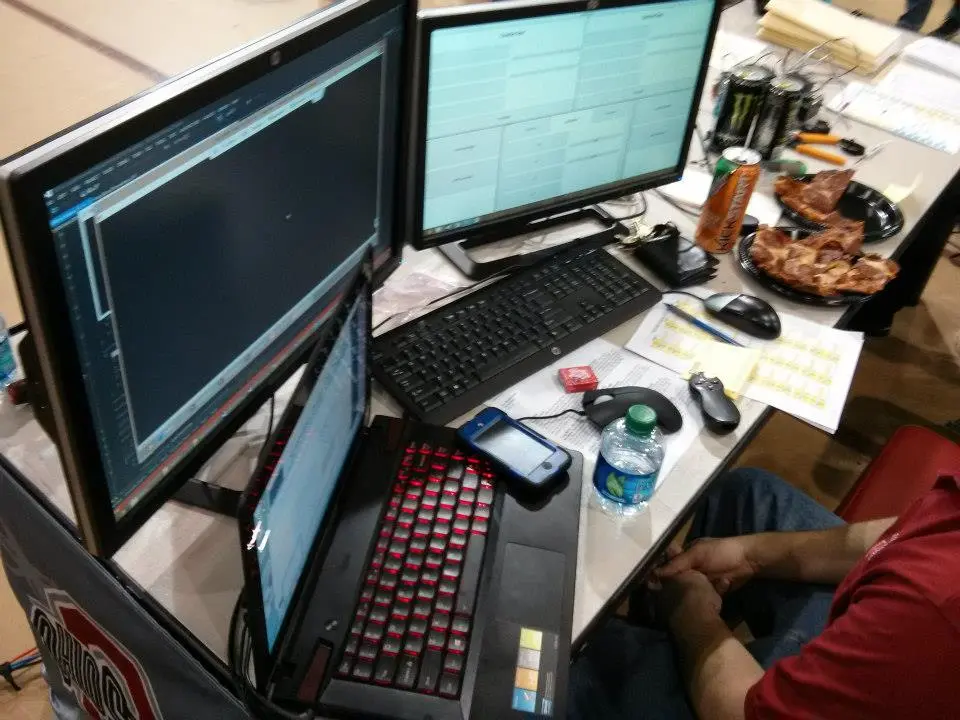

The course software is where I made the largest contribution. Our system required a substantial amount of hardware:

- The Proteus Microcontroller inside each robot

- The RPS mounted above each course

- Course hardware--microcontrollers and circuit boards that operated physical elements like stoplights and gates

- Windows 'course control PCs' that provided a touch-screen interface to begin and end runs or change course settings

- A 'master control PC' that provides some system-wide utilities and operates the scoreboard

I wrote a cross-platform Course Framework that allowed a course's hardware layout to be defined in an XML document. That document was loaded onto both the Windows PCs and the microcontrollers to keep the system state synchronized in realtime across the network and provide a touch-screen XAML interface for configuring the course.

The Course Framework represented every hardware component as an XML node with an address. The address format depended on the type of hardware. For example, a PC or microcontroller used an IP address, while custom circuit boards connected to the microcontrollers could be addressed by the index of an I2C port.

The system was connected in an absolute mess of switches and cables beneath each course. I have fond memories getting my hands dirty crawling around the under-course abyss to troubleshoot bad software, loose connections, and faulty hardware.

The competition was often hosted in large arenas, where a master control PC synchronized course status and the tournament bracket for the audience. During events, I spent most of my time behind that master control PC, ensuring everything ran smoothly.

Overall, leading the software team for the autonomous robot competition was an incredible experience. I learned a tremendous amount about leadership and software engineering while working with some of the most talented people I've ever met.

In later years, John Jackson and Michael Schulz took over as software leads and did an excellent job growing the program. Together with several instructors, we wrote a paper describing our approach, as well as improvements John and Michael introduced after I graduated: Modular System of Networked Embedded Components for a First-Year Engineering Cornerstone Design Project.